Across high schools in Pristina, students sit through civic education lessons that teach them about democracy, responsibility and their role in society. But one topic that directly affects their daily lives, consent, is nowhere to be found in textbooks or classrooms. While young people face growing risks of harassment, violence and misinformation, sexual education remains absent from Kosovo’s curriculum. This means many teenagers leave school without the basic knowledge they need to understand bodily autonomy, set safe boundaries, or seek help when something feels wrong.

The NGO “Follow Up” witnessed the consequences of this gap. During previous activities with youth, the organisation found that around 90% of students did not know what sexual consent meant, often misunderstanding the term as attraction because of how the word consent is used in everyday language. Students also said they had never encountered the concept in any subject, either at school or at home.

Evaluating How Consent is Reflected in Classes

To address this issue, “Follow Up” launched an initiative with the goal of understanding how consent is currently reflected in school materials and classroom practices, and what changes are needed to ensure students receive accurate, age-appropriate knowledge.

The first step was a detailed analysis of textbooks used in grades 10, 11 and 12. The findings revealed a consistent pattern that none of the books contained any dedicated lessons on sexual education or consent. Rather than engaging with real-life topics relevant to adolescents, the textbooks’ content remained highly theoretical.

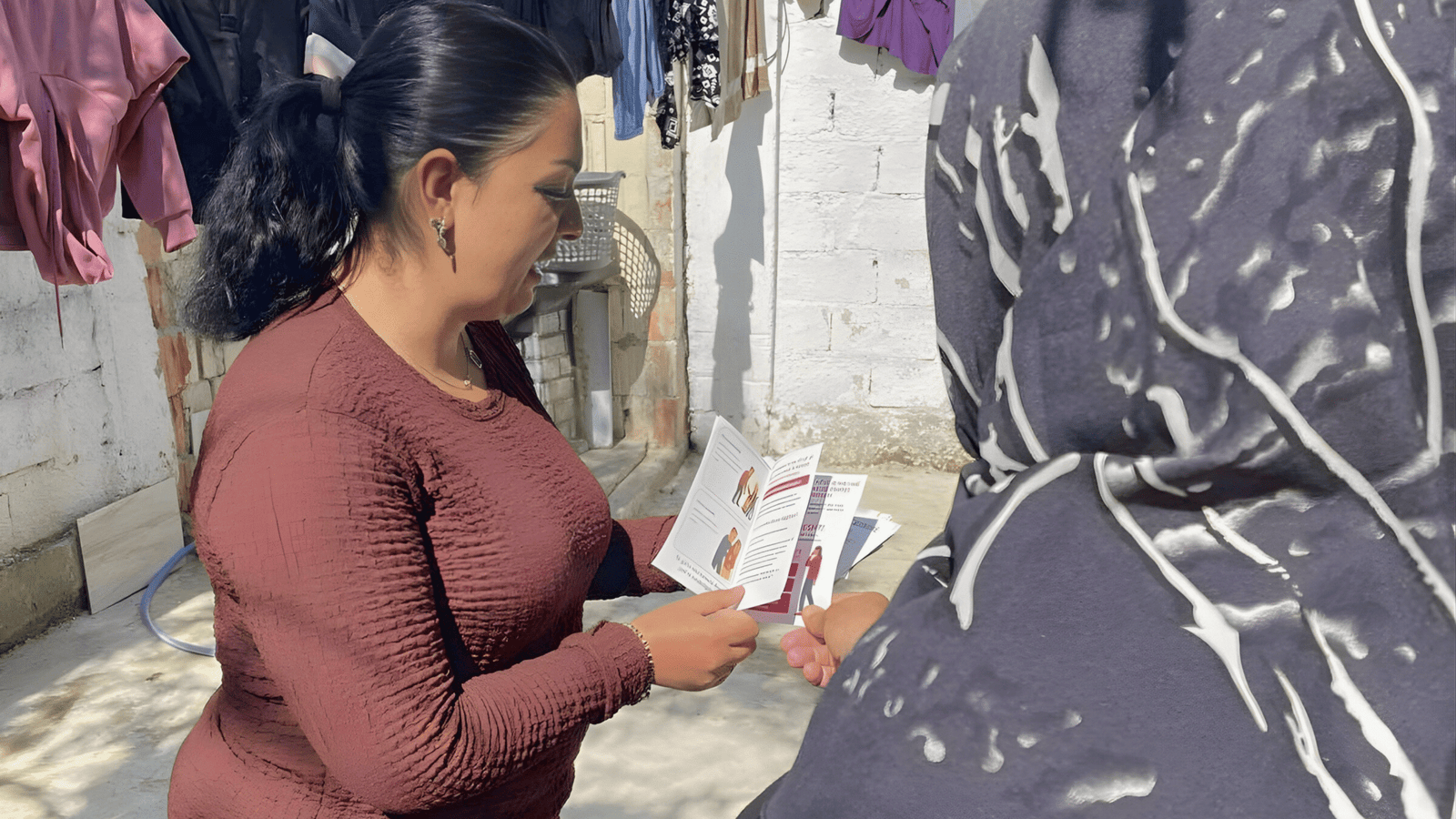

“Follow Up” also interviewed civic education teachers from several high schools in Pristina. None of them were familiar with the term consent before the interview. Once the concept was explained, they recognised its importance but acknowledged that they had never addressed it in their classes because it does not appear in the curriculum. While teachers expressed willingness to teach about consent in the future, they emphasised that they would need proper training to do so safely and effectively. Female teachers also reported observing or hearing from students about instances of sexual harassment, while male teachers said they had not encountered such reports, revealing differences in what students feel comfortable disclosing. Several teachers noted that they expected resistance from parents if sensitive topics were introduced, reflecting broader social discomfort around sexual education.

Observing How Gender Norms Appear in Daily Teaching

“Follow Up” also observed classes to understand how content is delivered in practice. The observations showed that girls and boys generally participated equally, and classrooms offered a comfortable atmosphere for discussion. However, gendered communication patterns appeared frequently. Teachers encouraged participation using gender-specific language, and disciplinary phrases differed depending on whether they addressed girls or boys. In every observed case, monitoring tasks such as keeping track of assignments were assigned only to girls. Additionally, leadership roles were consistently referred to using male-gendered titles, reinforcing subtle norms about who is seen as a decision-maker.

Turning Evidence into Meaningful Change

Through this process, “Follow Up” gathered the first evidence-based picture of how sexual consent is currently, and often not at all, integrated into the learning experience of high school students in Pristina. The findings were compiled into a policy brief designed to support institutional dialogue and future advocacy.

During the second phase of the project, “Follow Up” together with the Kosovo Women’s Network conducted an interactive training session with teachers, covering points and gaps identified during the classroom observations and interviews. They also organised a roundtable with participants from the Municipal Directorate of Education, the Centre for Social Work and the Municipal Coordination Mechanism against Domestic Violence, sharing key findings and recommendations from the policy brief and advocating for greater public discussion on the need for sexual education in the school curriculum.

By documenting what is missing and highlighting where teachers need support, “Follow Up” has opened the door for schools to begin addressing sexual consent in an informed, evidence-based way. In a society where silence around sexual violence continues to harm young people, this project marks an important movement toward classrooms where knowledge, respect and autonomy are part of every student’s learning experience.

Follow Up’s initiative “Analysis of the School Curriculum and Educational Approaches to Sexual Consent in High Schools” was carried out with support from the Kosovo Women’s Network’s (KWN) Kosovo Women’s Fund (KWF), financed by the Austrian Development Agency (ADA) and co-financed by the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida), in the amount of €14,900 from June to November 2023 and from January to December 2024. The initiative contributed directly to KWN’s Programme “Gender Transformative Education”.